Theme: Language and Gender Perception in the Art of Japan’s Heian Period

Language and Gender Perception in the Art of Japan’s Heian Period

As Japan’s Heian Period (794-1185) grew independent from the influence of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) of China, Japanese social and artistic identity flourished. Slowly shifting away from the influence of the Chinese court, Japan began to include their own sense of what it meant to be Japanese within East Asian culture. One major change was the creation of their own writing system independent from the Chinese characters of kanji, phonetic characters derived from kanji but in a simpler form called hiragana. In art, painting also incorporated the styles of both Chinese and Japanese art techniques called yamatoe. These two major changes to Japanese society during the Heian were closely associated with who was using them and who their audience was. Consequently, writing and painting styles also became coupled with gender relationships. Terms such as <onnae> (lit., “women’s painting”) and <otokoe> (lit. “men’s painting”) were used to distinguish particular styles of court painting and the types of writing with which these paintings were associated. Understanding how writing and painting was thought in of terms of gender relationships during the Heian Period and afterwards can provide insight as to how Japanese culture can be perceived then and now.

Japan created the hiragana writing system from the basic forms of Chinese kanji characters. Court etiquette prescribed that the Chinese kanji were considered most official (as were most Chinese traditions of the court), so hiragana became the written system used in private and unofficial documents. These documents tended to be diaries, poems, and other such personal expressions. Additionally, women were not expected to read or write Chinese characters as it was seen as too “masculine,” so their mode of written expression was usually hiragana. This became the framework for affiliating gender types with the written language. Similar to the onnae and otokoe terminologies, onnade and otokode (“de” meaning hand, translated: “women/men’s hand”) came to be used in relation to how hiragana and kanji were being used. However, hiragana and kanji were not exclusively defined as the writing of women and men, respectively. Hiragana, with its simple and expressive style of calligraphy, was considered acceptable for use by educated men when writing court poems and short stories, while for women the use of kanji was very rare. However these two writing systems were used, they formed the base material for Heian court paintings and therefore allowed for a general identification of who created and viewed them.

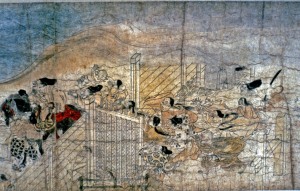

Serving as the source material for onnae and otokoe paintings, poems from both men and women were translated into visual forms. Onnae can be described as the elegant, layered painted ‘feminine’ style of Genji (Sekiya – figure 1). This is a painting from the first half of the twelfth century that is based on the text called Tale of Genji (c. 1000), a court story written by the court lady Murasaki Shikibu. The Tale of Genji suggests that the reading and exchanging of illustrated tales were important pastimes among court ladies, and that such paintings could also be created for political as well as aesthetic reasons.[i] In contrast, otokoe, exemplified by Shigisan engi (figure 2), was characterized by the quickly rendered, lively brushwork and animated activity of the scene. Figures in these two examples differ wildly. In the Genji piece, figures are calmly seated with repetitive and unremarkable facial expressions. Shigisan engi’s figures have wild facial expressions and the artist used a flatter style of non-layered pigment. Some scholars believe that onnae was a private and amateur activity, practiced by women, suggesting that otokoe is conversely the ‘public’ work of professional painters.[ii]

This notion of public, private, and gender distinction in the Heian period can help decipher how the Japanese culture fought to perceive itself then. Since there was an acceptance of “femininity” (hiragana) as the true mode of expression of Japan, the Heian Period classified its Japanese identity as “feminine” vis-à-vis China.[iii] Movement in and out of masculinity and femininity in Japanese art and writing can be akin to the fluctuating relationship between the “feminine” Japanese national identity and the “masculine” China. Yamatoe, the “art of Japan,” is the play of the feminine (Japan) within the masculine (China) modes of expression. Yamatoe was an extremely significant development in the Heian Period as it was the beginning of a uniquely Japanese expression of painting. It served to combine Japanese subject matter with Chinese technical execution, similar to the relationship of how femininity acts within masculinity in the use of kanji and hiragana characters.

The theme of one entity existing within another can be found in Japanese written language, art, and gender culture. Viewing works like Genji Sekiya and Shigisan engi from the perspective of how language and gender related during time period they were made can give insight to how Heian culture was structured. There was clearly a need for labeling forms of expression, either painting or writing, in a way that suggested there was a social counterpart (i.e. female to male), except that neither part (masculine and feminine) could be used independently from the other. There was a specific order to the Japanese court expectations of men and woman: even though they could blend with each other, they could still be considered separately “male” and “female.” This mixed dichotomy still exists in contemporary uses of gender, and equally with Japanese identity, so understanding the origins of the relationship can reveal how artistic expression is shaped by and shapes culture, language, and gender.

Susan Bopp

Figure 1, Genji, Heian Period.

Figure 2, Shigisan engi, Heian Period.

[i],[i]i Richard Louis Edmonds, et al. “Japan.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 25 Nov. 2009 <http://www.oxfordartonli4ne.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T043440pg9>.

3 Kaori, Chino. “Gender in Japanese Art.” In Gender and Power in the Japanese Visual Field, edited by Joshua S. Mostow, Norman Bryson and Maribeth Graybill, 17-34. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2003 [original article published in Japanese in 1994].

Search

You must be logged in to post a comment.